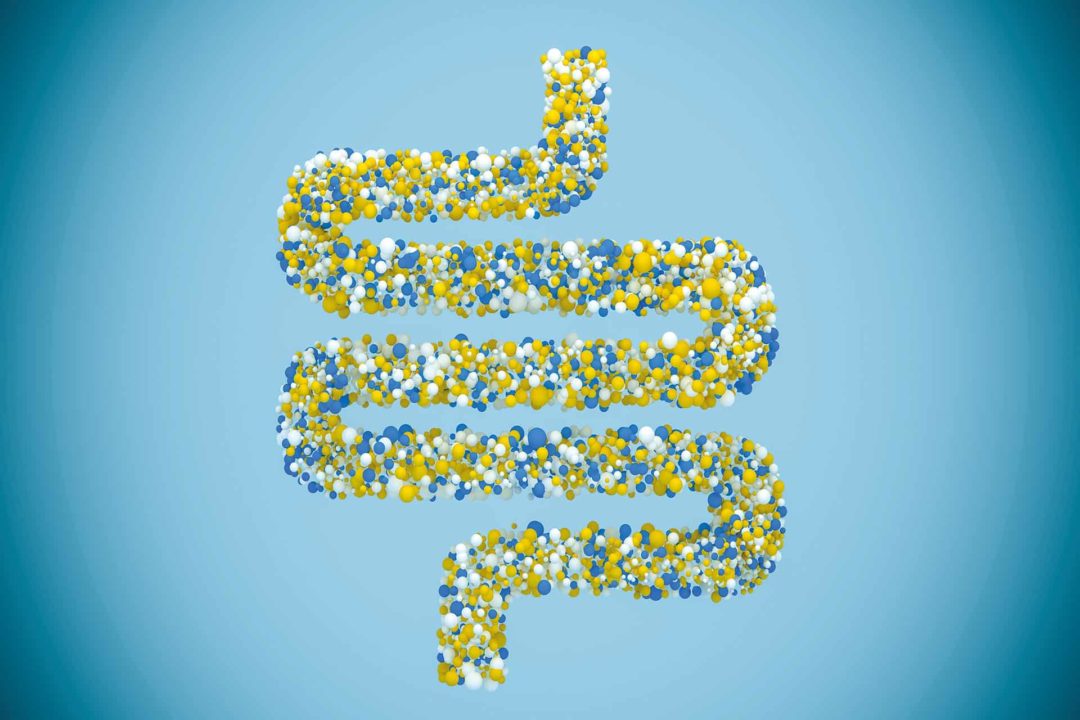

The human gut’s enteric nervous system (ENS) is a “second brain,” one that most people don’t know exists, according to Brian Gulbransen, an MSU Foundation Professor in the College of Natural Science’s Department of Physiology. A press release on the topic notes that the ENS is independent: Intestines could carry out many of their duties, even if they became disconnected from the central nervous system. And the number of specialized nervous system cells—specifically, neurons and glia—that live in a person’s gut is roughly equivalent to the number found in a cat’s brain.

While neurons are already known—they conduct the nervous system’s electrical signals—glia are not electrically active, which has made it difficult to work out what they do. However, in research published in theProceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,Gulbransen and his team revealed that glia act to influence the signals carried by neuronal circuits. "Thinking of this second brain as a computer, the glia are the chips working in the periphery," Gulbransen said. "They're an active part of the signaling network, but not like neurons. The glia are modulating or modifying the signal."

Related: #NaturallyInformed: Keynote Points to Diet As Top Healthy Aging Factor Global Survey Shows Increased Demand for Probiotics The Natural View: Kiwi Solutions for Digestive Health—Livaux & Actazin

Earlier this year, the press release states, Gulbransen’s team found that glia could open up new ways to help treat irritable bowel syndrome, which currently has no cure and affects 10-15% of Americans. Glia could also be involved in health conditions including gut motility disorders, such as constipation, or a disorder known as chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction—wherein people develop what seems like an obstruction in the gut, but without the actual obstruction; a section of the gut just stops working."This is a ways down the line, but now we can start to ask if there's a way to target a specific type or set of glia and change their function in some way," Gulbransen said. "Drug companies are already interested in this."