As a child of the sixties growing up in Los Angeles, I remember being mesmerized by the GE Carousel of Progress, an attraction in the heart of Tomorrowland at Disney’s Magic Kingdom. The musical peepshow into our future lured wide-eyed consumers (their impressionable future baby boomers in tow) into its theatrical belly of aspirational consumption by showcasing modern conveniences designed to make our lives easier.

Little did we know that a mere fifty-years later, GE’s promise of convenience would mutate into an addiction of disposability, inducing nothing short of a global health crisis.

But I digress.

I can hear the song now...It’s a great big beautiful tomorrow, shining at the end of everyday. There’s a great big beautiful tomorrow, just a dream away.

Some would argue the dream is now our nightmare.

The age of convenience has given birth to a throwaway culture, one in which manufacturers design and develop products for obsolescence and consumers embrace their expendability. It’s what Story of Stuff creator, Annie Leonard, refers to as the “Take, Make, Waste” system of industrial production and consumption.

With seven billion people in the world – projected to swell to nine billion by 2050 – what on earth will we do with all the discarded products and packaging? Landfills, check. Oceans, check check. Recycling and resource recovery, not so much.

In fact, only about one-third of all packaging and printed-paper waste (PPP) actually gets recycled. The majority winds up in landfills, incinerators and watersheds. The lack of effective recovery solutions for these resources results in squandered economic benefits including opportunities for material cost savings and new job creation in reuse and recycling.

The potential economic upside of resource recovery is only part of the equation. An unprecedented amount of plastic products from lighters to Legos are being found inside birds and marine life washed up on our beaches and shores. And according to studies conducted by environmental nonprofit, 5Gyres, the proliferation of seemingly innocuous plastic microbeads found in personal care products (facial cleansers, toothpaste) are carried through our drainpipes into water systems, poisoning ocean habitats and threatening human health as consumers feast on their favorite toxic sushi roll.

The carousel of progress has become a runaway train of waste. The question is, what can be done to stop it before it derails?

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR)

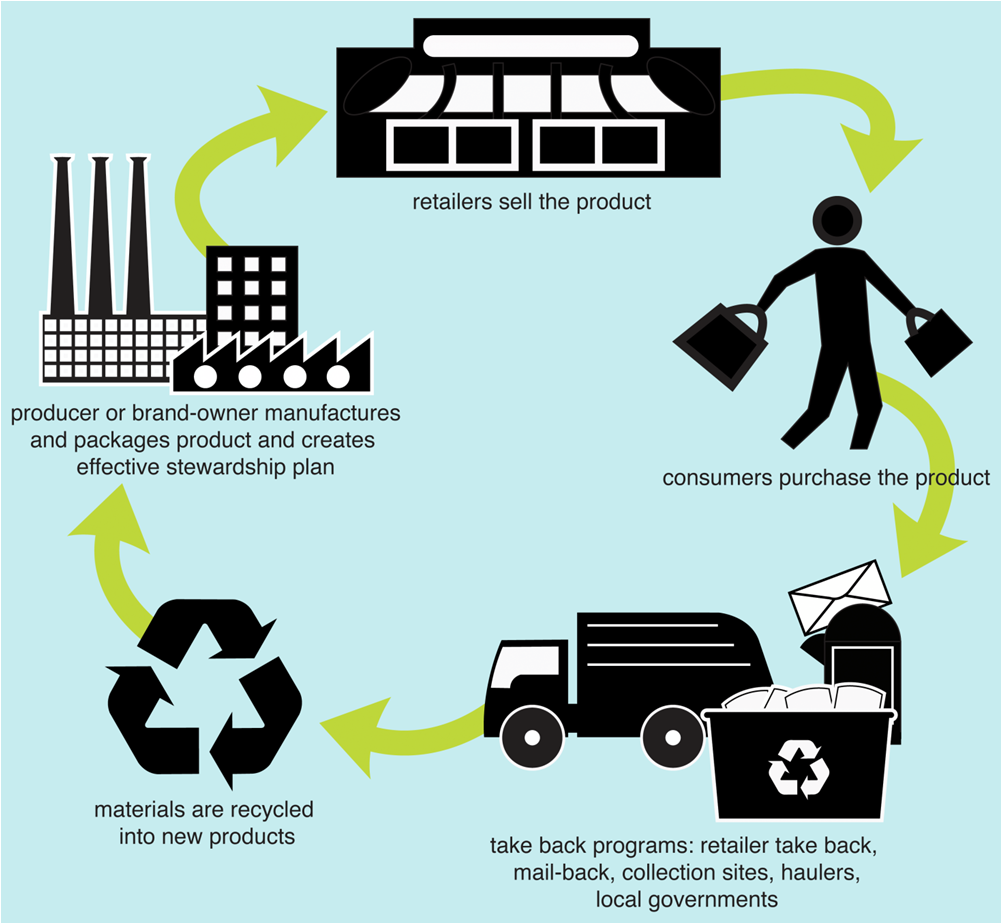

EPR is a strategy that places a shared responsibility for end-of-life product management on the producers and product chain contributors, while encouraging design changes that minimize a negative impact on human health and the environment at every stage of the product’s lifecycle. Incorporating the expense of treatment and disposal into the total cost of a product, EPR advocates such as the Product Stewardship Institute maintain that the most efficient and effective point at which to reduce waste and promote reuse, reduction and recycling, is at the product development stage when decisions can be made that will minimize the environmental impact of the product.

Under our current system of residential waste management, the government (i.e., taxpayers) foots the bill for disposal and recycling. In essence, manufacturers reap the rewards of selling their products and consumers get stuck with the bill. Public tax dollars pay for disposal and recycling programs to get rid of the waste. EPR shifts responsibility upstream, away from municipalities and regional waste authorities to the companies that put the products, packaging and marketing materials into the consumer pipeline, providing incentives to eliminate waste and pollution through product design changes.

By recovering product waste at the end of its lifecycle, EPR closes the loop on materials management by “upcycling” it as feedstock for new products or packaging.

For brand owners that manufacture their goods, having a larger supply of recycled material can lead to lower costs and enhanced supply security. Studies also suggest that EPR requires considerably less energy than manufacturing from virgin materials and encourages industry producers to become more innovative about product and packaging design.

Looking through a purely economic lens, our current cradle-to-grave model literally tosses billions of dollars worth of quality materials into the garbage. Moreover, we are also throwing away millions of American jobs. A 2011 report estimates that the United States can grow 1.5 million new jobs by increasing our nation’s recycling rate from 34% to 75%.

The Proof is in the Pudding

Currently, one billion people in 47 countries live in districts where producers bear some or all of the cost of managing packaging when consumers are finished with it. Recovery rates for packaging and printed-paper in the EU countries that have EPR compared with that of the U.S. supports the move toward this model.

* Glass: US, 33%; EU, 70%

* Metals: US, 55%; EU, 72%

* Paper: US, 62%; EU, 85%

* Plastics: US, 13%; EU, 33%

If the environmental upside isn’t inducement enough, consider the economic benefits associated with adopting an EPR strategy. In addition to substantially increased recycling rates, EPR can decrease energy use and reclaim billions of dollars of embedded value in technical and biological nutrients that are currently being buried in landfills or burned in waste incinerators.

There are multiple opportunities for brand owners in a strong, producer-financed EPR recycling program, such as competitiveness, innovation and maintaining a responsible reputation for the products they put into the consumer pipeline.

Does The Consumer Care?

A 2012 Neilson study on cause marketing, which surveyed 28,000 consumers in 56 countries, uncovered that a majority of respondents (66%) preferred to buy products from companies with robust and transparent environmental policies. The same number said they were willing to pay extra at retailers that use sustainable packaging, have eliminated plastic bags and use digital technology as opposed to paper for transactions.

In 2009, a report by global consulting firm Deloitte LLP determined that for 20% of consumers, environmental policies are more important than pre-established brand loyalty. While young consumers were the most adamant in their preferences for green companies, the Deloitte study found that those who actually make a point of buying from sustainable businesses were older (part of the baby-boomer generation), more affluent, typically had smaller households and were more educated. Additionally, consumers who said they value sustainability shopped 26% more often than their indifferent peers and were 29% more likely to buy more than they had planned on shopping trips. The study also determined that they were less price sensitive than the larger population.

According to Deloitte, 30% of consumers who do not shop with sustainability in mind would be willing to shop “green” if they were aware of which products are actually good for the environment. Many retailers, they found, don’t adequately publicize their green credentials when the reality is that consumers would like to hear more, not less, about a company’s efforts to help the environment. Consumers also expressed a desire for more labeling, and more in-store help from retailers to help them learn which products are made from sustainable materials and how that benefits the environment overall. Retailers that carry sustainable products and advertise their efforts could potentially turn many consumers into loyal green advocates.

Who’s Getting It Right?

From Crayons to cosmetics, Crocs to cookware, brands are taking back products and packaging for reincarnation into a second life. Patagonia, a pioneer in the practice of repurposing textiles, invites consumers to return garments beyond repair and recycles them into products of equal value. Ford turns old floor mats into engine parts. And the rubber meets the road with tire recycling, used for everything from skateboard decks to landscaping mulch. B-Corps such as Method are committed to resource-recovery practices that put them in an elite class of companies to achieve Cradle-To-Cradle product certification and supplement leader Rainbow Light uses its trademark 100% post-consumer recycled Eco-Guard packaging to keep 10 million bottles from entering the waste stream every year.

The concept of squeezing more value out of materials for both economic and environmental purposes is not new however, the growing interest in material recovery among multinational corporations is propelled by the daunting reality of resource scarcity, the proliferation of more stringent zero-waste regulations and the financial windfall that comes with cost-effective reuse strategies.

Our planet is a finite resource. To create a sustainable future, we must rethink how we use these materials. We must move from our current cradle-to-grave process to what is now referred to as a circular economy. In this reimagined state, resources will continuously be reused with no net effect to the environment.

Of course, we must address society’s addiction to overconsumption before circular economy models can achieve any sort of scale. To that end, millennials are gravitating to a Sharing Economy or peer-to-peer ecosystem, giving birth to companies such as Airbnb, Lyft and Thredup, in the service of reducing expenses along with our collective carbon footprint.

So what might today’s Carousel of Progress look like? Imagine a solar-powered stage built from recovered resources and filled with products made from repurposed materials, shared by an interconnected community of consumers, suppliers, manufacturers and municipalities committed to a zero-waste lifestyle.

Now we just need a song...perhaps there’s an old toe-tapper we can recycle?

WF

Colette Brooks is the chief imagination officer at Big Imagination Group.

Published in WholeFoods Magazine December 2015